Introduction

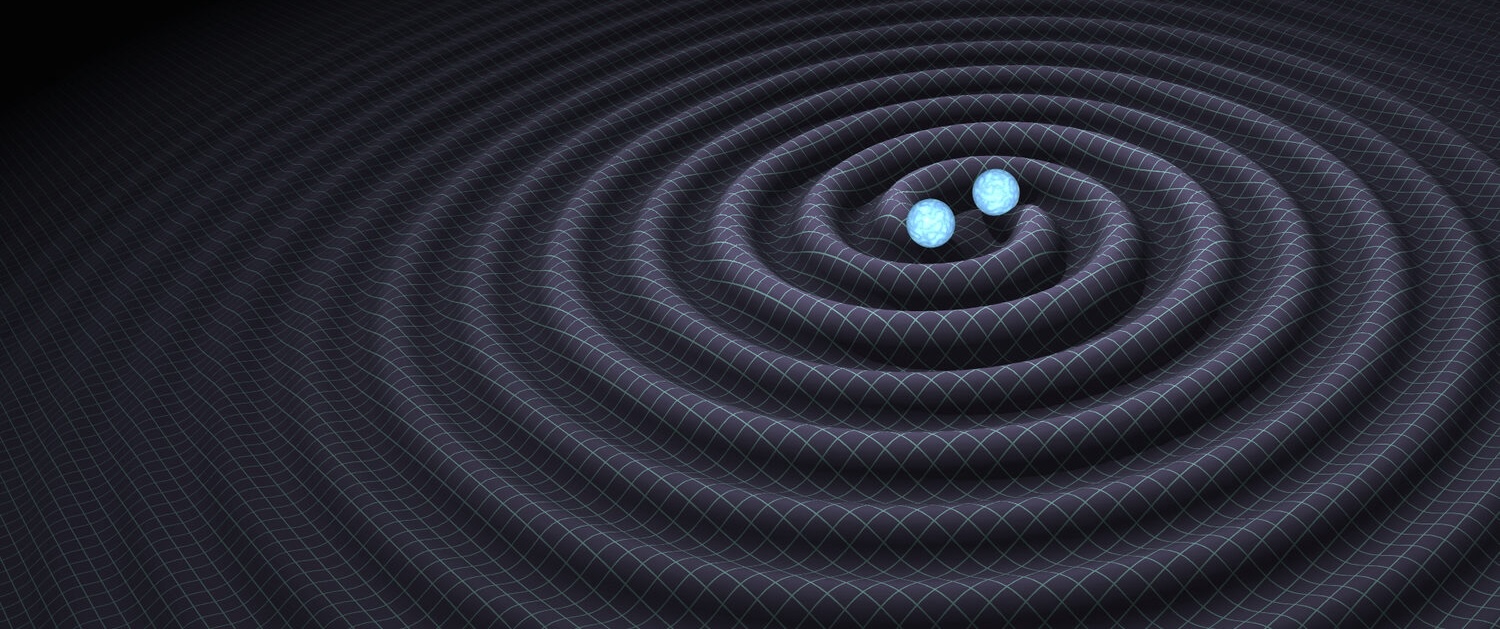

Despite the extraordinary success of the Standard Models of Particle Physics and Cosmology, our understanding of basic aspects of fundamental physics is still incomplete. The nature of dark matter and dark energy, the origin of the matter/anti-matter asymmetry, the explanation of neutrino masses, and the reality of cosmic inflation remain important open questions. In order to solve these issues, scenarios involving physics beyond the Standard Model are being investigated and are under scrutiny in astro-particle physics experiments, from colliders to telescopes. Many of these “Beyond the Standard Model” scenarios would also imply the existence of novel phenomena in the very early stages of the Universe, potentially leaving footprints that we can look for in the form of a gravitational-wave background.

LIGO/Virgo/KAGRA (LVK) data allows us to search for signs of the gravitational-wave background that could have been generated by these early-Universe mechanisms, such as first-order phase transitions, cosmic strings, domain walls, a stiff equation of state, axion inflation, second-order scalar perturbations, primordial black holes, and parity violation. We discuss briefly each of these phenomena below.

Phase transitions, cosmic strings and domain walls

Ever since it began, the Universe has been expanding and steadily cooling down, and in early times, the Universe underwent changes in its fundamental state – analogous to what happens with water when liquid water becomes ice. As the temperature of the universe dropped, it underwent a series of phase transitions, entering states with fewer symmetries, i.e. where the original uniformity of the forces of nature has fragmented into distinct and specific characteristics. In this process, topological defects, such as cosmic strings and domain walls may appear. A cosmic string is a one-dimensional object, the energy of which is concentrated along a line. It is analogous to the cracks which can appear in ice as the water freezes.

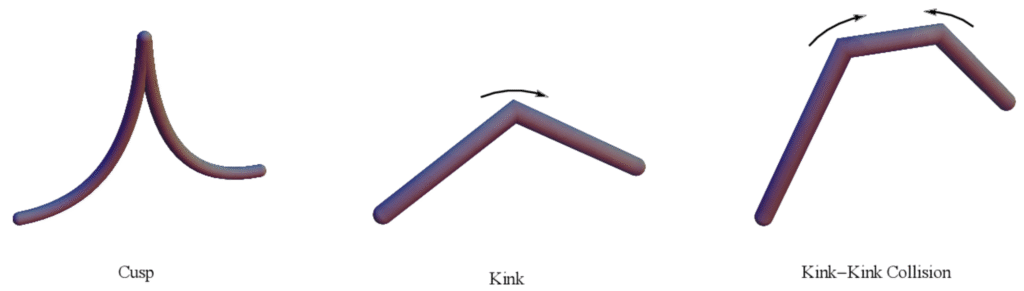

Figure 1 shows a cusp and a kink on a cosmic string. When cusps and kinks are formed and accelerate on a cosmic string, gravitational waves are emitted. The collision of kinks also creates gravitational waves. A domain wall is a two-dimensional object, a boundary that separates two domains. It is a place where the universe’s fundamental properties had to transition from one stable state to another.

Figure 1: Cartoon illustrations of cusps, kinks and kink-kink collisions, which dominate the gravitational-wave production from cosmic strings at high frequencies. [Image credit: Long, Hyde and Vachaspati]

A “stiff” equation of state

In the standard cosmological model, the Universe was first dominated by relativistic particles (i.e. particles moving at speeds close to the speed of light) before entering a matter-dominated era in which the energy density of the Universe became dominated by particles moving at slower speeds. Some high energy physics models imply that these different eras may have been preceded by an unconventional sequence of epochs during which the relationship between the pressure and the energy density of the Universe (known as its “equation of state”) was highly unusual, with the pressure of the cosmic fluid as high as its energy density: this scenario is called a “stiff” equation of state.

Axion inflation

To address some puzzles and unanswered questions associated with the Big Bang Cosmological model, it has been proposed that the Universe experienced an early period of very rapid expansion, known as cosmic Inflation, during which the Universe grew exponentially fast. Among the various inflationary models that have been considered, in one called axion inflation the exponential expansion is driven by a hypothetical particle called the axion that is motivated by ideas from high energy particle physics. Axions are also candidates for cold dark matter, being extremely light, electrically neutral and interacting very weakly with normal matter.

Second-order perturbations

The Universe on large scales is homogeneous and isotropic, in accordance with what is known as the Cosmological Principle. However, on smaller scales the Universe is not so regular: there are perturbations – variations in both the geometry and the matter content of the Universe – that it is believed have led to the existence of structures (i.e. galaxies and clusters of galaxies) and voids. There are different types of cosmological perturbations. Fluctuations in the density and pressure of the cosmic fluid are called scalar perturbations, while ripples in spacetime itself are tensor perturbations, otherwise known as gravitational waves. In Albert Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, gravity is non-linear. Matter creates gravity, but gravity – because it contains energy – creates even more gravity. As a result of this, two cosmological perturbations expressed in their simplest mathematical form can interact with each other to produce a more complicated perturbation, known as second-order.

Primordial black holes

Primordial black holes are hypothetical black holes that could have been formed in a variety of different ways in the early Universe. Their mass spans a wide range and they could also form binaries – i.e. pairs of primordial black holes that are gravtiationally bound to each other. These objects have gained a lot of interest since they are one of the most plausible candidate for dark matter.

Results: Searching for the signatures of non-standard cosmological models

All the above cosmological sources could produce a gravitational-wave background. Searches for such a background in LVK data can constrain the parameters of the cosmological models at energy scales above the ones we can reach using particle accelerators.

In addition, parity violation is the idea that the laws of physics might not be the same when you look at a mirror image of a given process. An example is CP Violation, in which the principle of CP, or charge conjugation-parity, symmetry (which states that the laws of physics should be the same if a particle is interchanged with its antiparticle while its spatial coordinates are inverted or “mirrored”) is violated. Some cosmological models motivated by high energy physics may result in the production of gravitational waves that violate parity. LVK data can therefore also be used to search for parity violation processes in the early Universe.

In our new publication we use data from the first four LVK observing runs to search for a gravitational-wave background from all the cosmological sources we have described above. At the same time, we have also considered a gravitational-wave background contribution from weak and distant astrophysical sources, such as compact binary coalescences – the mergers of e.g. binary black hole and binary neutron star systems – throughout the Universe.

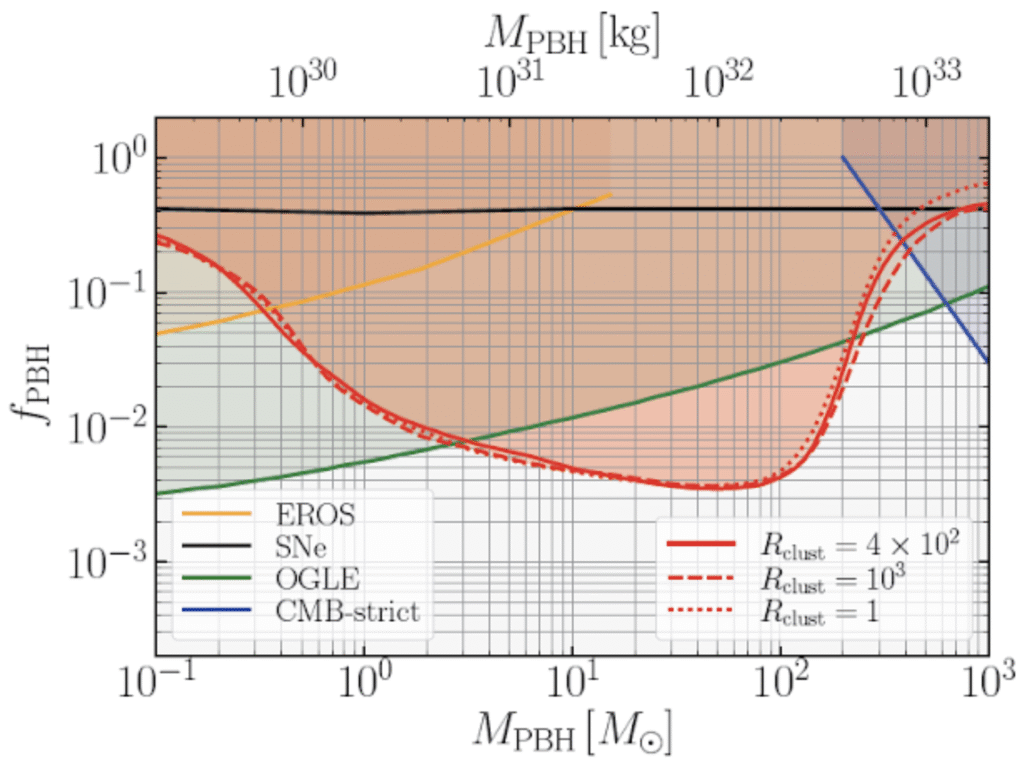

Figure 2 (Fig. 14 from our publication): plot showing the constraints from our analysis on fPBH, the fraction of dark matter composed of primordial black holes today, as a function of the primordial black hole mass MPBH in units of the Sun’s mass. The red shaded region is excluded by our analysis with a probability of 95%, i.e. we are 95% sure that the fraction of dark matter composed of primordial black holes cannot be larger than the values traced out by the solid, dashed and dotted red curves – which correspond to different model assumptions about the rate at which primrodial black hole binary mergers occur. We can see from the Figure that the constraints on fPBH from our gravitational-wave analysis are, in certain mass ranges, significantly stronger than from other astrophysical probes, such as microlensing surveys (EROS, OGLE), supernovae lensing constraints (SNe) and measurements of the cosmic microwave background (CMB-strict).

No signal was found, but our analyses were still able to set important constraints on the models that we tested. An example of these constraints, for the case of primordial black hole models, is shown in Figure 2 (Fig. 14 from our publication).

Find out more

- Visit our websites:

Back to the overview of science summaries.