While our knowledge of the population of compact binary mergers continues to grow with already 50 objects released in the GWTC-2 catalog, there remain many other possible sources of yet-to-be-detected gravitational waves (GWs). As the worldwide network of GW detectors also increases to now include LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA, the possibilities of finding GW signals from different astrophysical phenomena continue to grow. Here we consider transient gravitational waves on a “long” time scale, i.e., GWs whose energy is spread over seconds to several minutes. One such source is provided by compact binary coalescences with large eccentricity. The gravitational wave emission from these sources is well understood, but there are computational difficulties in searching for their signals with template waveforms as is done for binaries with negligible eccentricity. There are also less well-understood sources, such as deformations on magnetar surfaces and matter asymmetrically falling into a newborn neutron star. Detection of gravitational waves from any of these sources would bring deep, new insights into poorly understood phenomena. For example, detection of gravitational waves from magnetars would help constrain the strength and shape of their magnetic field. Because models that account for all of the important physics of such phenomena are not generally available for these sources and are at least more uncertain than for compact binary mergers, the techniques used to search for their signals are designed to operate making minimal or no assumptions. This enables the detection of signals of unknown shapes, required due to the wide range of potential sources, at the cost of less sensitivity to weaker signals. Of course, the possibility of as-yet-unpredicted sources is one of the most exciting.

The analysis and the results

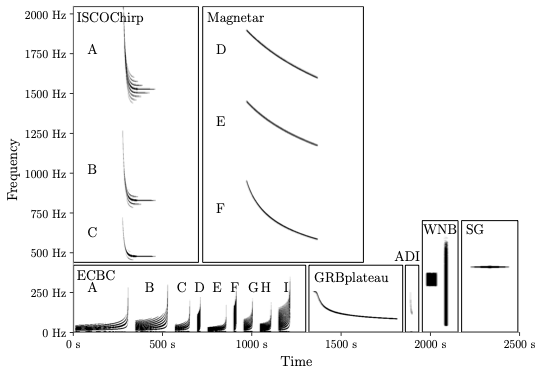

We search for a range of possible durations and emission frequencies for these long-duration gravitational-wave transients using three different pipelines. Using multiple pipelines has many benefits: (1) it provides robustness against noise glitches of instrumental or environmental origin that mimic the characteristics of the targeted signals (non-Gaussian transient noise events), as each pipeline has an independent treatment of such noise features and (2) different possible models/signal shapes are covered with different effectiveness by different pipelines and pipeline sensitivities to both astrophysical and “ad-hoc” models can be compared to identify the possible limits of each of them. Ad-hoc models considered include white noise band-limited (WNB) and sine-Gaussian (SG) signals. We also use astrophysical models for the possible signals emitted by a variety of objects. These include magnetars formed in a binary neutron star merger (Magnetar), black hole accretion disk instabilities (ADI), newly formed magnetars powering a gamma-ray burst plateau (where X-rays produced by the gamma-ray burst afterglow show a phase where the X-rays do not decay; GRBplateau), eccentric compact binary coalescence waveforms (ECBC), and broadband chirps from the accretion around rotating black holes within the innermost stable circular orbit (ISCOchirp). We considered different masses and eccentricities for the ECBC waveforms, different masses of the central black hole for ISCOchirp waveforms, and rotational frequencies and ellipticities of the magnetar due to its magnetic deformations for the Magnetar waveform. The durations of these signals vary from 6 s (ADI-B) to 470 s (GRBplateau), and their time-frequency spectrograms are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Time-frequency spectrogram of the reference waveforms used in this search (see main text). They cover signals with a durations range from 6 s (ADI-B) to 470 s (GRBplateau).

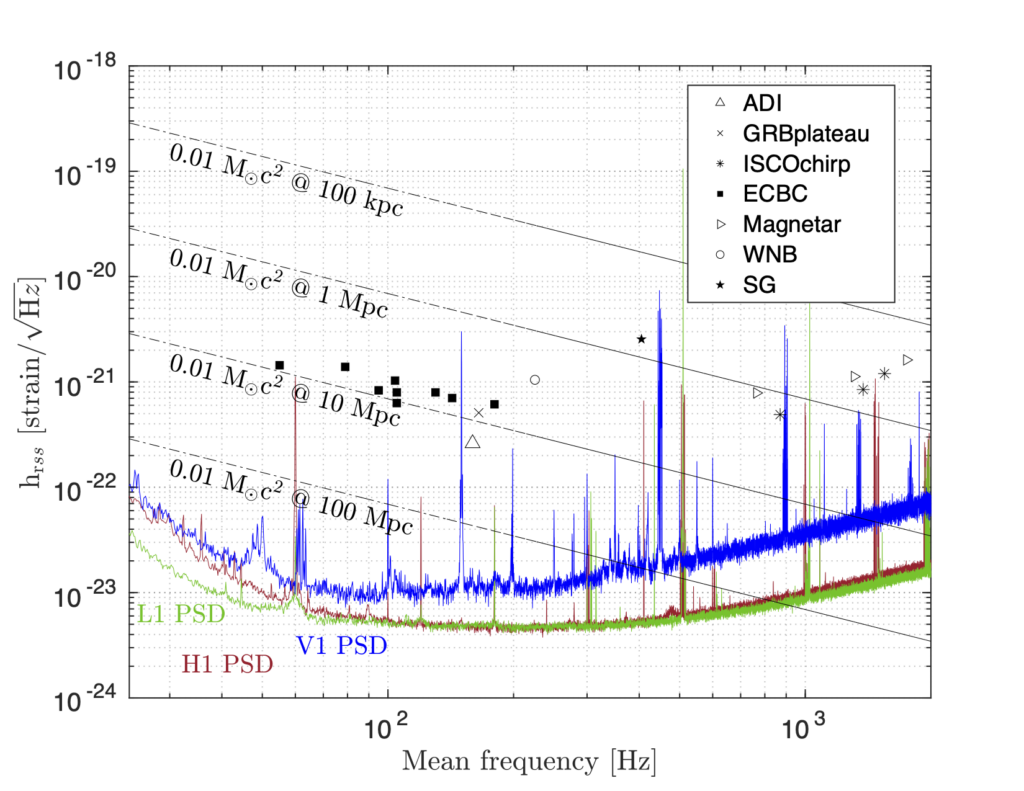

None of the pipelines found any significant events coincident in both the Hanford and Livingston detectors. The loudest events in the 204 days of data when both detectors were operating are consistent with being noise. The Virgo detector did not contribute to this search due to its relatively lower sensitivity during the third observing period O3 (see Figure 2), but we expect it to be included during the next observation period, O4.

Figure 2: The GW root-sum-square strain amplitude (where the square root of the sum of squared amplitudes at different times is taken) versus mean frequency at 50% detection efficiency and a false alarm rate of 1/(50 years). The red, green, and blue curves are the averaged amplitude spectral noise densities for Hanford (H1), Livingston (L1), and Virgo (V1) detectors to show that the search results follow the detectors’ sensitivity at different frequencies. The dashed lines show the hrss, as a function of the frequency, associated with the conversion in GW of the energy equivalent to 1/100 of a solar mass (M⊙) at different distances in megaparsecs (Mpc).

Given the absence of a detection, we derive upper limits on the gravitational-wave amplitude of long-duration gravitational-wave transients corresponding to the considered reference signal, using the results from the pipeline that is most sensitive to each model. We also set limits on the rates of the eccentric binary coalescences occurring in the Universe (see Figure 3). The limits we set are improved by about a factor of 2 over the last analysis. While detection would be preferred, the upper limits still inform us of the possible rates for these exotic systems. We look forward to O4 to find new astrophysical sources of gravitational waves.

Figure 3: Upper limits at 90% confidence level on the rate of eccentric compact binary coalescences as a function of the distance. Only the best result is shown for each waveform. The inset shows the ratio of the rates with respect to O2 results for ECBC A to ECBC F.

Find out more:

- Visit our websites:

- Read a free preprint of the full scientific article. also available on arXiv.org.

- science summary for the observing period O1 (2017) version of the search

- science summary for the observing period O2 (2019) version of the search