Gravitational waves (GWs) are ripples in the gravitational field, predicted to exist by Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity. A neutron star is the extremely dense remnant of the core of a massive star. Born in a supernova explosion, neutron stars are some of the most interesting objects in the universe. They have the mass of about the sun but the size of a small city. All the forces of nature — gravity, the strong and weak nuclear interactions, and electromagnetism — play huge roles in their properties and behavior.

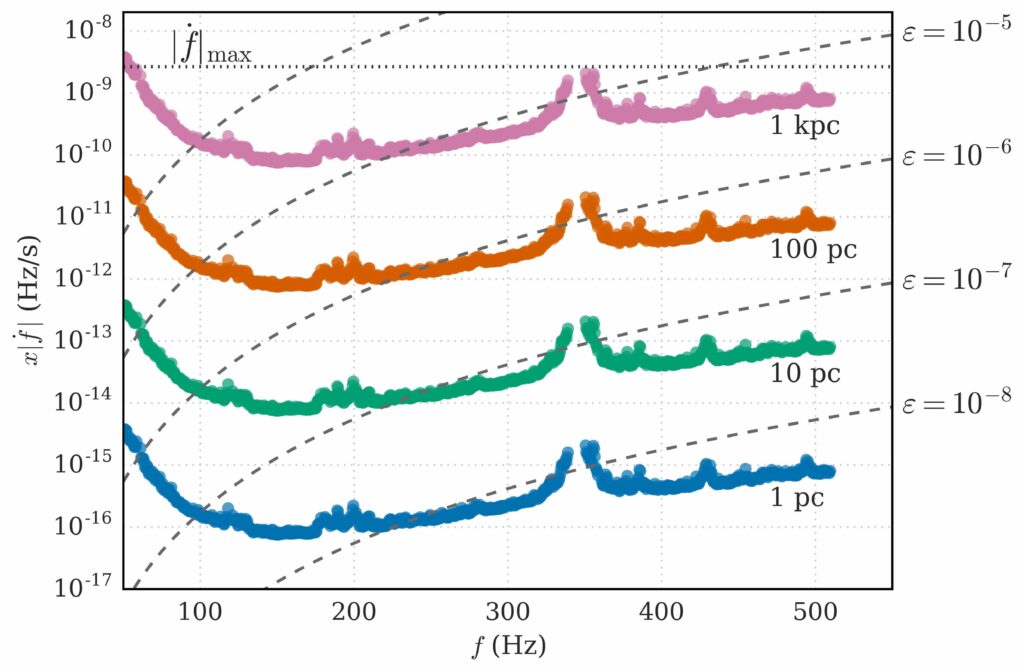

Rapidly rotating neutron stars are expected to emit GWs continuously as they spin, if they are not perfectly spherical. The amount by which a neutron star deviates from being perfectly spherical can be described by a parameter called the ellipticity. The larger the ellipticity, the stronger the GWs emitted by the neutron star. Neutron stars are expected to have very small ellipticities: the astrophysics of their structure predicts that they are among the most spherical objects in the universe, with ellipticities of 10-5 or lower. The best human technology produces spheres that are close to perfect at that level (for example, the quartz sphere gyroscopes that flew on Gravity Probe B). For normal neutron star material, the maximum deformation that the neutron star crust could sustain before collapsing is about 10 cm. Nevertheless, by analyzing a long stretch of data from the LIGO detectors with carefully prepared software, we could pick even such a very weak signal out of the detector noise. At present, a few thousand neutron stars in our Galaxy have been identified as pulsars by their radio, X-ray or gamma-ray emissions, but our Galaxy is estimated to contain roughly 100 million neutron stars that are not observed through their electromagnetic emissions. With a search for continuous GWs that scans the entire sky, we have the potential to make new detections of neutron stars and learn about their structure.

GWs from rapidly spinning neutron stars will be detected at some specific (but unknown) signal frequency, close to a perfect sine wave. We nominally expect the GW signal frequency to be twice the neutron star spin frequency, but it could also be at any multiple of the spin frequency. The spin frequency is the number of revolutions of the neutron star per second, measured in Hertz (Hz). These all-sky searches need to look for unknown sources located everywhere in the sky, for a wide range of possible signal frequencies and frequency derivatives, where the frequency derivative is the rate of change of the frequency. The ideal data analysis strategy used to extract the faint continuous wave signals from the detector noise is given by the matched filtering method, applied to many months of data. Matched filtering is a data analysis method in which the data are correlated against a simulated waveform in order to try to identify that signal buried in the detector noise. The ideal data analysis technique requires a huge amount of computing power, more than is available to the LIGO Collaboration, when data stretches of the order of months or years are used and a wide fraction of the parameter space is searched over. Hence, to search for these signals using a realistic amount of computing power, we use a “hierarchical” approach in which the entire data set is broken into shorter segments and afterwards the information from the different segments is combined. We can use segments of a few days, allowing for very sensitive searches.

Because the search is very computationally intensive, it has been carried out with the Einstein@Home project. This is a volunteer based distributed computing project which relies on members of the public to donate their idle computing power to GW searches. Hundreds of thousands of host machines, that contributed a total of approximately 25000 CPU (Central Processing Unit) years, were needed to carry out the computations.

This all-sky search for GWs from isolated neutron stars uses data from the Initial LIGO detectors (LIGO Hanford in Washington and LIGO Livingston in Louisiana) collected in 2009 – 2010 during the sixth Initial LIGO science run (S6). In this search, we focused the immense computing resources of the Einstein@Home computing project on an all-sky search for GWs from spinning neutron stars in the most sensitive frequency range of S6 data, from 50 Hz to 510 Hz. Under the assumption that the GW frequency is twice the neutron star frequency, this means we are looking for neutron stars spinning between 25 and 260 revolutions per second.

This search considers neutron stars with frequency derivative ranging from about -26 × 10-10 Hz/s to 3 × 10-10 Hz/s. We mainly consider negative frequency derivatives, as we would expect the spin frequency of the neutron star to decrease over time as it loses energy. For example, if a neutron star is spinning at 50 Hz and emitting GWs at 100 Hz, after 12 years the signal frequency will fall to as low as 99 Hz. The observed frequency derivative can differ from the actual frequency derivative due to radial acceleration of the neutron star, which is why we consider a small range of positive frequency derivatives.

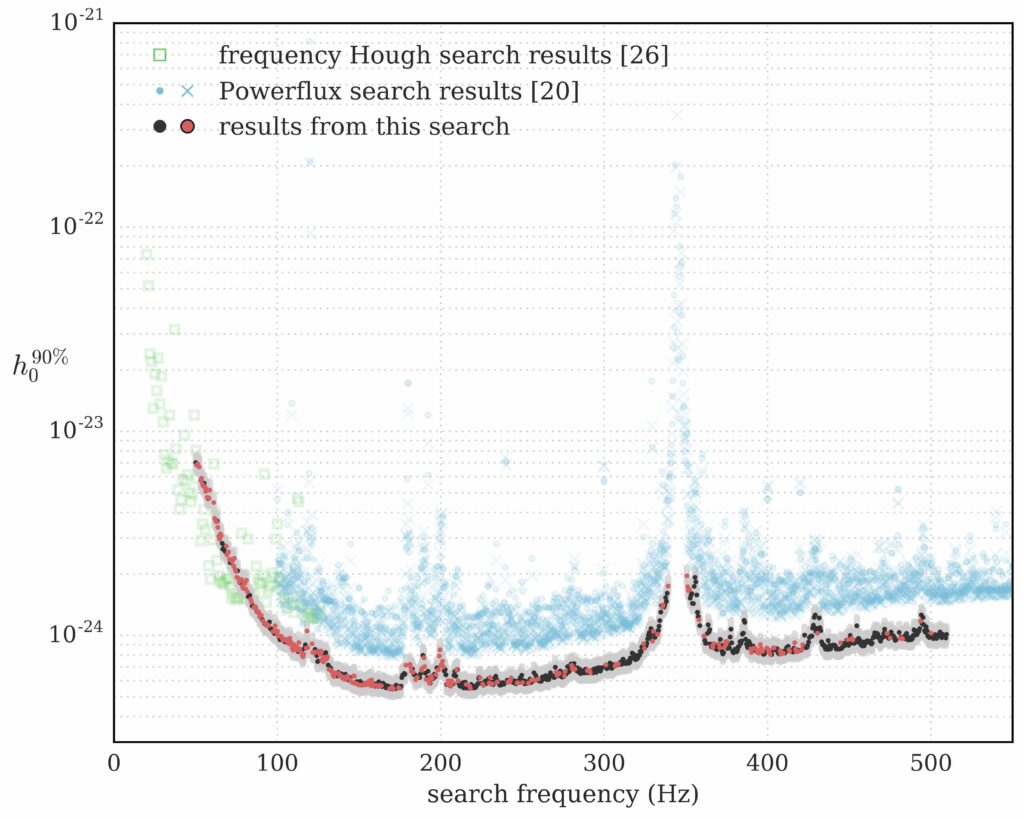

Figure 1: This plot shows the upper limits on the GW strain amplitude for this search (black and red) and for two other all-sky searches: one on the same data, referred to as the Powerflux search (blue), and one on contemporary data from the Virgo detector, referred to as the frequency Hough search (green). The curves represent the source strain amplitude at which 90% of simulated signals could be confidently detected.

No GW signals were detected in this search, presumably because there are no neutron stars emitting strongly enough in our frequency band to be detected at our sensitivity level. We quantify that conclusion by calculating upper limits on the GW strain amplitude: this is the smallest GW signal amplitude that we would have been able to detect with a 90% confidence. Since we have not detected any signal, we can exclude the existence of signals of the type that we have searched for with amplitudes greater than our upper limit value. For example, at the frequency where the detector is most sensitive, between 170.5 and 171 Hz, we can exclude the presence of signals with a GW strain amplitude of 5.5 × 10-25 or higher with a 90% confidence level. We can only compute upper limits with a finite statistical confidence level because detector noise is random and thus has to be described using probability and statistics. As shown in Figure 1, the upper limits set by this analysis (black curve) are ~ 1.5 to 2 times more constraining than those set by other all-sky searches between 100 and 510 Hz, at the time of this publication. This improvement is primarily thanks to the significant computing resources of the Einstein@Home project, but also partly due to the methods and post-processing techniques used in the Einstein@Home search.

Figure 2: This plot shows the ellipticity of a source at different distances (indicated by the colors) that would have been detected by this search, with 90% confidence, if it was emitting continuous gravitational waves.

If you have been running Einstein@Home on your computer, we thank you very much for your donated computations! If you haven’t been participating, but want to, you can get started by going to https://einsteinathome.org/.

Read more:

- Freely readable preprint of the paper describing the details of the full analysis and results: Results of the deepest all-sky survey for continuous gravitational waves on LIGO S6 data running on the Einstein@Home volunteer distributed computing project, by B. P. Abbott, et al. (LIGO and Virgo collaborations).

- More recent results from an Einstein@Home all-sky search using Advanced LIGO data are available here.