In 2024, one of the best old friends of radio astronomers on the sky presented a very exciting opportunity for gravitational-wave (GW) searches: a neutron star known as the Vela pulsar experienced a “glitch”, a kind of hiccup in its otherwise steady radio signals. The physical processes behind pulsar glitches are still not fully understood, and detecting their aftermath in GWs could be a crucial step to solving this puzzle.

Pulsar glitches

The Vela pulsar, located about a thousand light-years from the Earth and not much older than ten thousand years, belongs to a particularly fascinating type of star: it is an extremely dense leftover of the supernova explosion at the end of a massive star’s life, compressed so much that it became a neutron star. It also spins around so quickly (over 11 times a second) and has such an intense magnetic field (over a trillion times stronger than the Earth’s) that it emits strong beams of electromagnetic radiation. As these beams sweep past the Earth with every rotation, radio telescopes (and those observing in other wavelengths) pick up pulsed signals – hence the term pulsar. The pulsar slowly loses energy over time and slows down, and a small part of this energy loss could be explained by continuous GW emission.

Figure 1: The nebula surrounding the Vela pulsar and the jet launched by it. Composite image of X-ray (credit: NASA/CXC/Univ of Toronto/M.Durant et al.) and optical (credit: DSS/Davide De Martin) observations.

But in the case of the Vela pulsar, this very regular series of pulses shows an unusual feature every two years or so: during a so-called glitch: the pulsar’s rotation suddenly speeds up again. Such glitches are known from various other pulsars, but Vela was the first pulsar observed to glitch, has displayed some of the strongest glitches known, and is among the pulsars most frequently producing these strange hiccups. Still, from telescope observations alone, glitches remain very enigmatic events. They are likely linked to powerful “starquakes”, to superfluid effects in the dense interior of the star, or a combination of both, but the details remain unknown.

In particular, from the side of the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA Collaboration (LVK), we got excited about the latest large glitch of the Vela pulsar, which was picked up by radio telescopes in late April 2024, while the LIGO and Virgo detectors were in full observing mode. Since Vela is a constellation of the Southern sky, the two radio telescopes that provided precise timing information about this glitch were those of the Argentine Institute of Radioastronomy and the Mount Pleasant Observatory of the University of Tasmania.

Figure 2: The four observatories participating in this work: two radio telescopes in Argentina and Tasmania, and the two LIGO gravitational-wave detectors in the US. Credits: Argentine Institute of Radioastronomy, University of Tasmania, LIGO Laboratory (Caltech/MIT)

Why should pulsar glitches cause gravitational waves?

Due to their extreme density and rapid rotation, neutron stars are also exciting as possible GW sources. Besides faint long-term signals from their slow spindown, stronger signals could also be produced over shorter durations whenever the star suffers some violent event – such as a pulsar glitch. And indeed, there are several models of how a pulsar glitch could produce GWs.

First, a neutron star can ring like a bell with various types of oscillations. The strongest are called “f-modes”, short for “fundamental modes”. Glitches can trigger such f-modes, just like a bell rings when struck with a hammer. As the neutron star vibrates, we expect it to emit GWs in the Kilohertz range, which last just for a fraction of a second or at most a few seconds.

Second, the glitch could also deform the shape of the neutron star. This can be imagined as the formation of a kind of “transient mountain” that, for a while, rises out of the mostly smooth shape of the pulsar at rest. Once this happens, the now uneven rotation would also send out GWs. But due to the immense gravity of the neutron star, the mountain would eventually dissolve again. These GWs would be at much lower frequencies (twice the rotation rate of the pulsar itself, so about 22 Hertz for Vela) and weaker than those from f-modes, but can potentially last for days or even months, so that we still have good chances to detect their overall effect.

Gravitational-wave searches

With their fourth observing run, the LIGO detectors have reached such impressive sensitivity that we now for the first time have a realistic chance to find GWs caused by an event like a glitch from the Vela pulsar. To grab this chance, we used a mix of different methods to make sure we can find something despite the big unknowns about what actually happens during the glitch. Using a number of different search algorithms for each class of signal is important to ensure robustness in the face of unknown physics and complicated detector noise patterns.

We used three different algorithms to search for signals of at most seconds or minutes in duration. These cover a broad frequency range and do not assume specific signal models, so they are sensitive to the expected f-modes as well as other short-lived signals a perturbed neutron star could emit.

In addition, four other algorithms are designed for long-duration signals, from half an hour up to four months in possible duration. These focus on signal frequencies of about 11 Hertz and about 22 Hertz, as expected for example from the “transient mountain” scenario.

First physical constraints, and future prospects

Unfortunately, despite the record-breaking sensitivity of the LIGO detectors in their current observing run, we did not yet find convincing signs of GWs from the Vela pulsar. However, this set of results represents an important milestone: for the first time, we were sensitive enough to place physically meaningful constraints on the gravitational radiation after a pulsar glitch. This means that if the full energy released at the glitch event would have gone into producing GWs, we should have found something. This is true across the full range of long-duration signals, while for the f-mode case we only reach such novel constraints at low frequencies below a Kilohertz, while most realistic neutron star models say the emission should be at higher frequencies.

As a result, the best insight we got into the Vela pulsar from not having found anything in this search came about for the “transient mountain” scenario. In this case we can say that either:

- the idea that the specific changes seen in the pulsar’s radio emission after the glitch are caused by such a “transient mountain” is not correct, or

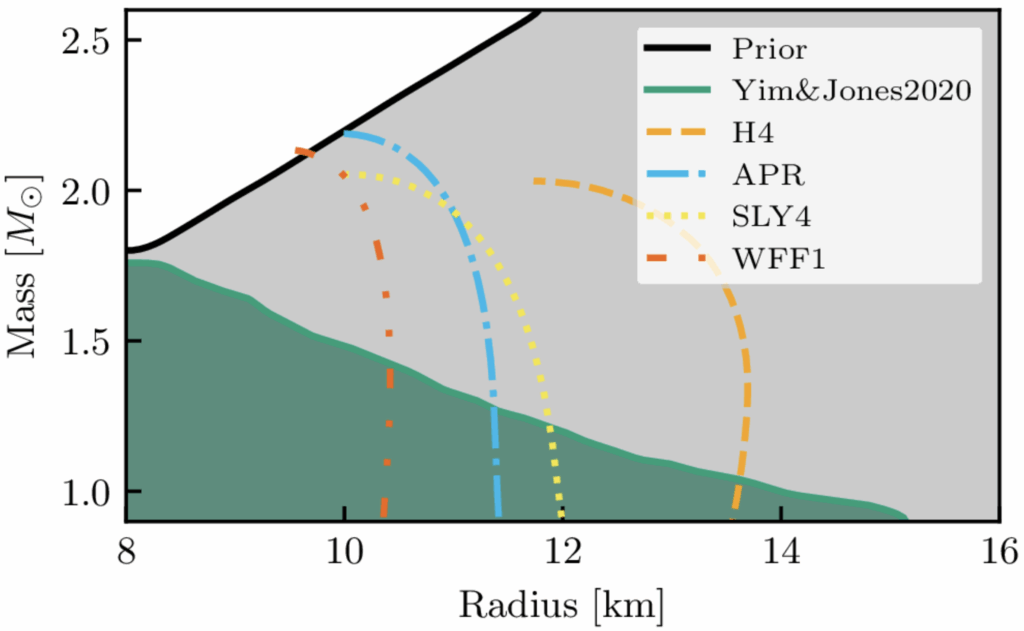

- if this idea is correct and GWs were emitted as predicted in this scenario, then the pulsar must be on the smaller and lighter end possible for this type of compact stellar remnant. This is because a bigger or heavier neutron star would have emitted a signal from its “transient mountain” that we should have found – see figure 3.

These results are consistent with those from other neutron star observations (such as the famous GW170817 binary merger), which already tell us that the Vela pulsar must be packing a mass higher than our Sun’s into a sphere with a radius of under 15 km – not much more than most cities on Earth!

Figure 3: (figure 7 of the scientific article): With the LIGO GW detectors not having found any signal from the Vela pulsar after its 2024 glitch, this tells us that either some of the emission models are not quite correct, or that this neutron star must have certain properties that make the GWs weak enough for us to miss. In particular, our results on long-duration signals tell us that either the specific changes seen in the pulsar’s radio emission after the glitch are not caused by a “transient mountain”, or if they are, that the pulsar cannot have mass or size exceeding certain limits. In this graphic, we see those limits on the radius (horizontal axis) and mass (vertical axis). The large area under the solid black line is the set of possible values we initially considered, while the green shaded area towards the lower left is what remains after taking into account that we have not observed long-duration signals but where we still assume that a mountain has emitted some GWs according to the specific model we have been testing. The dashed and dotted lines correspond to some theoretical predictions of how the mass and radius of a neutron star could be related to each other.

After this milestone result, we can expect that future pulsar glitches occurring when GW detectors have become even more sensitive will yield even better constraints. And eventually, a direct detection of GWs from a glitching pulsar will help unravel the mystery of why Vela and its cousins experience these strange hiccups.

Find out more

- Visit our websites:

- www.ligo.org

- www.virgo-gw.eu

- gwcenter.icrr.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ (KAGRA)

- www.iar.unlp.edu.ar (Argentine Institute of Radioastronomy / Instituto Argentino de Radioastronomía – in Spanish)

- ra-wiki.phys.utas.edu.au UTAS Radio Astronomy Group (Mt. Pleasant Radio Observatory)

Read a free preprint of the full scientific article here or on arXiv.org.

Back to the overview of science summaries.