Dark matter makes up 85% of the total matter in the Universe, but it is completely invisible to us. And yet, we can measure its effects on a variety of celestial objects: it roams around each galaxy and prevents stars from flying out of their orbits, it changes the directions of light rays from far-away galaxies, it guides the formation of the large-scale structures of the Universe, and it has even left imprints in the cosmic microwave background, the farthest and oldest photograph of the Universe, taken when it was only a few hundred thousand years old.

Figure 1 The estimated current matter and energy content of the Universe. The dominant contribution overall comes from so-called “dark energy”, which is driving the accelerated expansion of the Universe. The remaining contribution, of about one third, comes from dark matter and ordinary matter (i.e. atoms) with dark matter comprising about 85% of the total matter content. (Image credit: ATLAS Experiment, CERN)

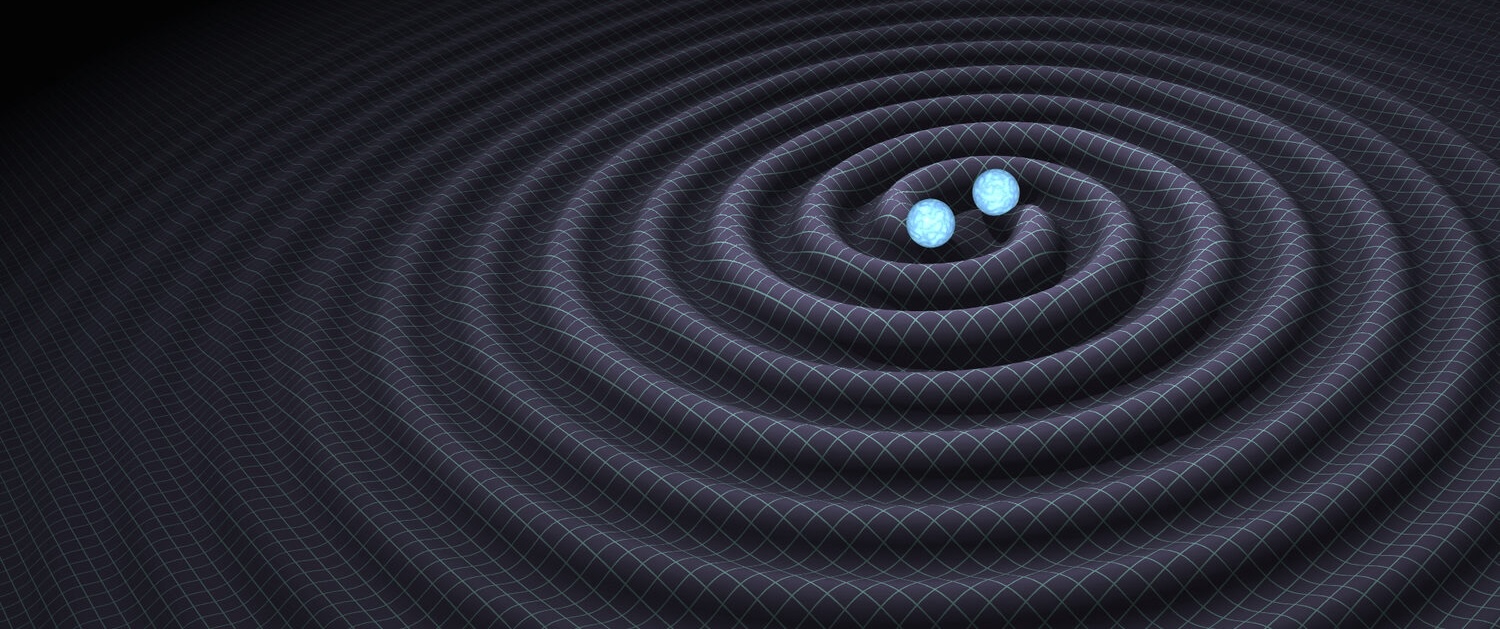

LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA were designed to search for gravitational waves from merging black holes and neutron stars, asymmetrically rotating pulsars, exploding stars, and combinations of all of these sources. But, these detectors are so sensitive that they could also observe dark matter that interacts directly with them. Here, we search for a specific type of dark matter, dark photons, that could have a mass that is twenty orders of magnitude smaller than the electron mass. On earth, these particles would be moving at around 300 km/s, and there would be so many of them, O(1050), that they would interact with protons and neutrons, or just neutrons, in the detector’s mirrors, and cause a time-dependent, oscillatory force on the mirrors. The mirrors are in different locations relative to the incoming dark photons, and are separated by three or four kilometers; thus, each mirror will move in a slightly different way and imprint a signal.

The signal will be at approximately one frequency because the mass of each dark photon particle is fixed. Dark matter is also always flowing through the detectors, which means that dark photons are constantly interacting with the particles in the mirrors. Therefore, the signal is continuous, always on, and at an almost fixed tone. In practice, the signal’s frequency shifts by a very small amount randomly over time because each dark photon is travelling at a different speed when it interacts with the detector.

Figure 2 (from the erratum published in Physical Review D in 2024): Upper limits on the strength of the coupling of dark photons to the mirrors in the interferometers, as a function of signal frequency. (While the search also used data from the Virgo detector, these upper limits are for just the two LIGO detectors.) Coupling strengths above the red and black/blue lines have been ruled out by this study: the lower the limit, the more constraining our searches are. We have used two methods (called the “cross correlation“ and “BSD“ methods) to search for dark photon dark matter, which have provided consistent results. These limits are a factor of 10-100 better than those from other dark matter experiments (MICROSCOPE and Eot-Wash) at many frequencies. The dark photon coupling strength is expressed in terms of a fraction of the electromagnetic coupling.

Our work uses data from the third observing run of Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo to determine if and with what strength dark photons could couple to the interferometers. Although we have not detected a signal, we can place upper limits on this coupling as a function of the possible mass of the dark photon. In this analysis, the coupling of dark photons to interferometric gravitational-wave detectors has been measured to be no bigger than one part in 1040 of the electromagnetic coupling for all ultralight masses we considered, even as low as one part in 1047 at some masses! Our constraints are about 10–100 times better than those obtained with some experiments that were designed to search specifically for dark matter. Our measurements of the coupling of dark photons to LIGO and Virgo give us insight into how dark matter influences the present Universe and how it could have formed.

Figure 3 (figure 2 in the paper): Our search initially found some apparent candidate signals, but they were all confidently discarded because they were due to instrumental noise artifacts. As an example, this figure shows a measure of data quality (the power spectral density) from the two LIGO detectors, with clear periodic structures in the Hanford detector (“H1”) and a narrow peak in the Livingston detector (“L1”), both coming from known instrumental issues. These caused the apparent signal candidate found at the frequency indicated with the vertical line, which hence was excluded as a dark matter signal.

Find out more:

- Visit our websites:

- Read a free preprint of the full scientific article here, or on arxiv.org.

- Read the full scientific article published in Physical Review D, with an erratum correcting figure 3.