Gravitational waves from small black holes

LIGO and Virgo have now detected many pairs of large black holes (BHs) from the gravitational waves generated as they spiral together and merge, but can we also see very small black holes this way?

Using LIGO and Virgo data from 1 April to 1 October 2019 we searched for BHs as light as one fifth of the Sun’s mass, employing 3 different matched-filter based pipelines. This search covers a larger mass and spin range for the BHs than the previous analysis. We did not find any valid candidate signal for compact objects under one solar mass.

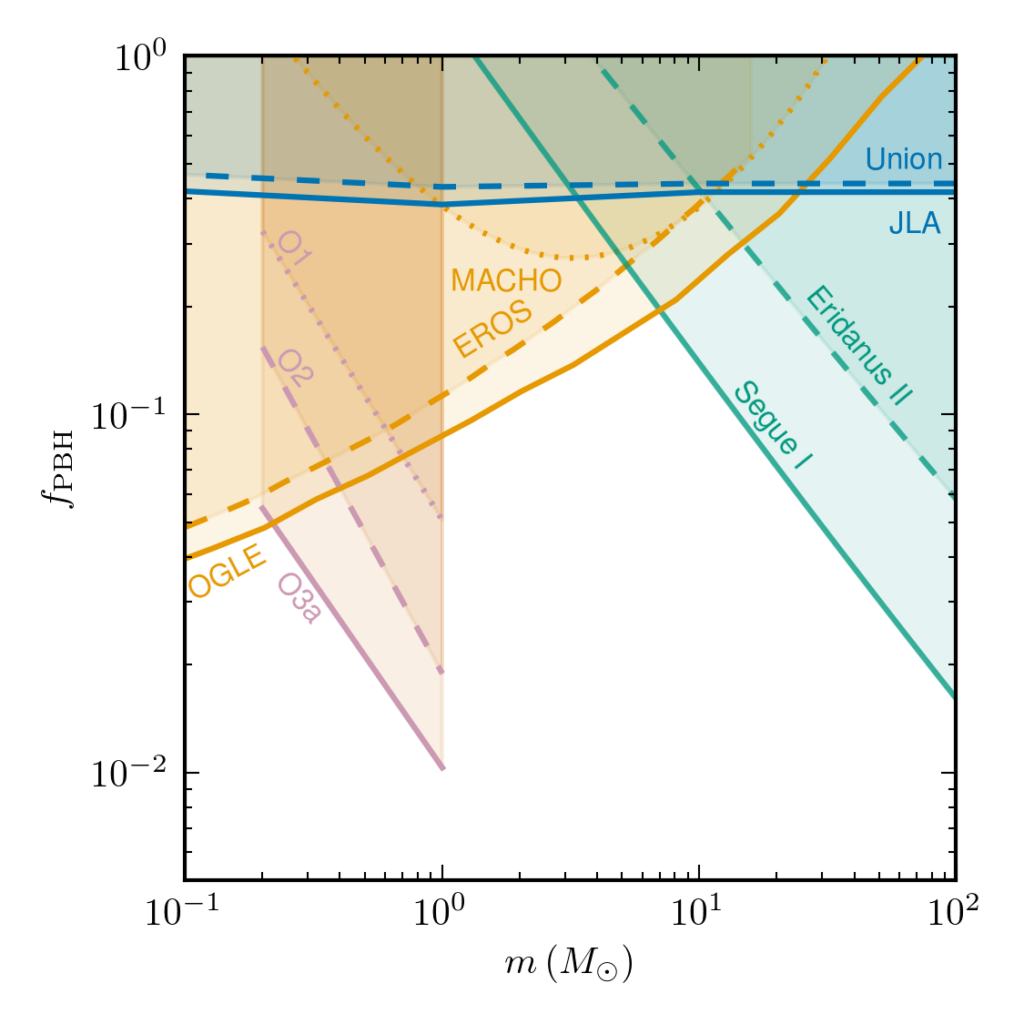

Figure 1: Constraints on the fraction of dark matter in primordial black holes. The horizontal axis shows the mass of the black hole, the vertical axis shows the upper limit on the fraction of the dark matter that those black holes can account for. See the main text for the meaning of the coloured regions.

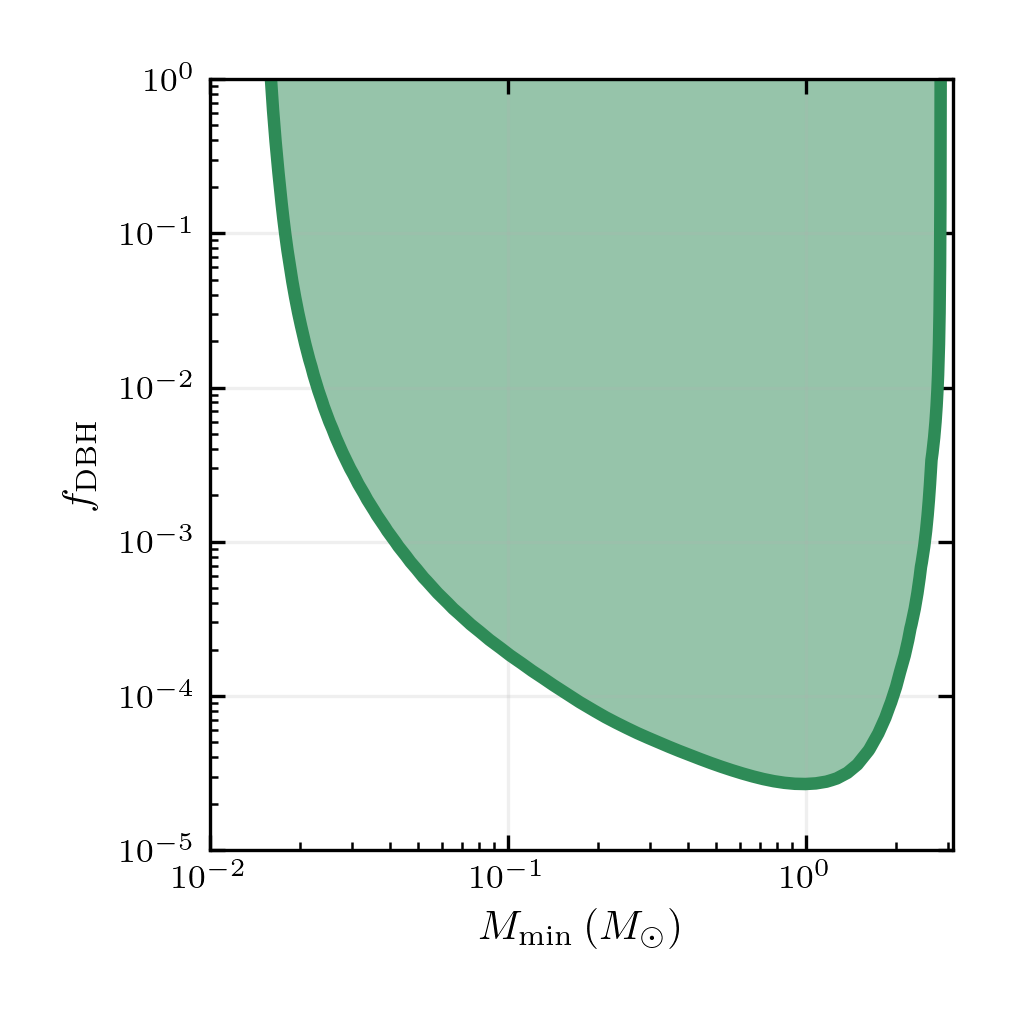

The non-detection of these signals allows us to set new upper limits on the merger rate density of subsolar-mass BHs. These limits can be recast into limits on the physical parameters of any astrophysical model that could generate subsolar-mass binaries. In Figure 1 we show the constraints on the abundance of primordial black holes as a dark matter component. We consider a population of equal-mass BHs; the horizontal axis shows the mass of the BH in each model and the vertical axis shows the constraints on the fraction of dark matter in primordial BHs (fPBH). The different coloured lines in the figure represent constraints set by different experiments: the orange lines are constraints from microlensing experiments; the green lines are from observations on the dynamics of the dwarf galaxies Segue I and Eridanus II; the blue lines are from supernova lensing; finally the violet lines are the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) results from the first and second observing runs (O1 and O2), and the new constraints we set with this analysis from the first part of the third observing run (O3a). Our new results significantly improve microlensing and supernova lensing constraints in the same mass region, as well as our previous constraints from O1 and O2; we have obtained an upper limit on the abundance of these BHs as a function of their mass at formation, with fPBH below 5%. In Figure 2 we show the same constraints for BHs formed from the collapse of particle dark matter halos (DBH). The lowest upper limit is found at one solar mass, where fPBH is below 0.002%.

Figure 2: Constraints on the fraction of dark matter in black holes formed from the gravitational collapse of dark matter halos. The horizontal axis shows the minimum possible mass of black holes formed from this mechanism.

If LIGO-Virgo detectors observe gravitational waves from a binary system of two compact objects where at least one of the two component masses is subsolar, this result will challenge our understanding of stellar evolution or possibly hint at new physics.

Life and turbulent death of stars

Stars spend most of their life in an equilibrium state, where the outward pressure generated by nuclear fusion reactions sustains the matter against the inward gravitational force. Depending on the mass of the star, the nuclear reactions can last millions or even billions of years. Heavier stars shine brighter and consume their fuel faster, living a shorter life.

The nuclear fuel for young stars like our Sun is mainly hydrogen. When a star has converted all the hydrogen in its core into helium, nuclear reactions can no longer sustain the matter against the gravitational force, and the star starts to collapse. The contracting star reaches higher temperature in its innermost regions and, if the mass is sufficiently large, the star can start new nuclear fusions involving helium, or even heavier elements. The star passes through different equilibrium phases, until eventually the conditions for igniting further nuclear reactions are no longer satisfied. At this point the star will start to collapse, and stellar evolution models predict different final fates for the star, depending again on its initial mass. For light stars with roughly less than 10 solar masses, the electron degeneracy pressure is high enough to halt the gravitational collapse and they become white dwarfs. In contrast, heavier stars become neutron stars and very massive stars, with initial mass larger than roughly 25 solar masses, turn into BHs.

Stellar evolution models predict that neither BHs nor neutron stars can be subsolar-mass compact objects. As a matter of fact, the lightest neutron star observed so far has a mass slightly higher than one solar mass, while BHs arising from stellar evolution are heavier objects.

What might subsolar-mass compact objects be?

Several models relate subsolar-mass compact objects to dark matter. Dark matter is a hypothetical form of matter that does not emit any light, making it difficult to detect. It is dark in a similar way as BHs, and it can be perceived only through gravitational effects.

We do not know what the building blocks of dark matter are, but the latter is thought to account for the majority of the matter in the Universe. Among the proposed candidates for dark matter, an appealing possibility is that it could comprise new types of fundamental particles that primarily interact through gravity. In this context, theorists predict that dense regions of particle dark matter can collapse to BHs of masses that cannot be explained with the known astrophysical processes. Alternatively, ultralight particles can clump together and form very low-mass compact objects known as boson stars. Furthermore, dark matter particles can gravitationally interact with neutron stars and trigger their collapse to BHs, and eventually form a subsolar-mass compact object. All these possibilities are currently under investigation.

Another possibility is that dark matter is composed not only of particles, but of BHs formed in the early stages of the Universe, through the gravitational collapse of overdense regions. These are known as primordial BHs, which can have masses below one solar mass.

Analysis of the second portion of O3 (called O3b) is currently in progress and might eventually unveil a subsolar-mass merger event, or further improve the constraints on the abundance of these objects in the Universe. Furthermore, Advanced LIGO, Advanced Virgo and KAGRA are going to enter a new observing run in 2022, with more sensitivity than ever!

Find out more:

- Visit our websites:

- Read a free preprint of the full scientific article here or on arXiv.org.