Gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime produced by the mergers of compact binaries, like those detected by the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) collaboration—were a prediction of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Einstein’s theory also tells us that matter curves the space and time around itself so that any signal travelling through that region will be deflected by this curvature. This process, known as gravitational lensing, is mathematically similar to the lensing of light as e.g. it passes through glass (a phenomenon on which you may be relying to read these words!) The gravitational lensing of light by massive objects in space has been observed for over a hundred years, and has become a routine part of the astronomers’ toolkit, but so far lensing by gravitational waves has not been observed.

In this study, we have searched for signatures of gravitational-wave lensing in the new binary black hole events detailed in our latest LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA catalog (GWTC-4.0), which includes detections made during the first part of the fourth LVK observing run (O4a).

What signatures does gravitational lensing leave on gravitational waves?

Since all matter causes the curvature of space and time, there is a wide array of different objects (corresponding to a wide range of different masses) that could lens a gravitational wave signal on its journey to Earth. These range from individual stars, through fields of stars, all the way to galaxies and clusters of galaxies—and it is not surprising that, with possible lenses spanning such a range of different mass scales, the potential signatures of gravitational lenses on gravitational waves are varied as well.

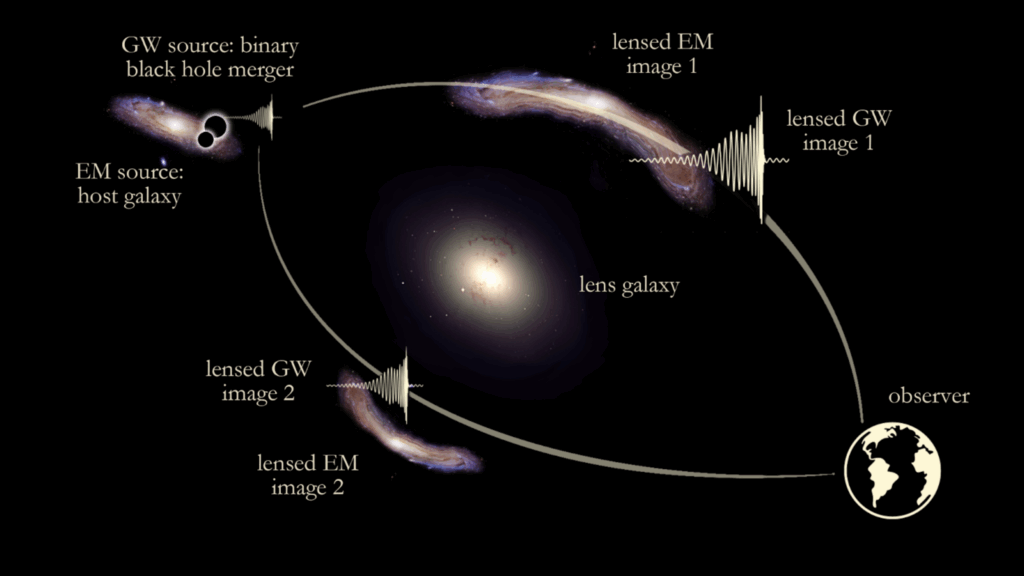

Consider first the heavier end of the scale, that of galaxies and galactic clusters (which are on the order of hundreds of millions of solar masses or more). If a gravitational-wave signal passes closely enough to such a massive object, it experiences what we call strong lensing, where multiple copies of that signal are produced. This phenomenon is shown in Figure 1, which illustrates the effect of strong lensing for both a light signal (from the host galaxy of the gravitational-wave source) and the gravitational-wave signal itself. These copies of the signal each travel along their own trajectory and experience different parts of the gravitational field produced by the lensing object, and so we observe them at different times with different magnifications—which changes the amplitude of the gravitational wave, making the source appear either nearer to or further away from us. However, this leaves the shape of the signals otherwise unchanged aside from a global phase shift—similarly to how, when looking through glass, the reflections are flipped.

Figure 1: Schematic illustrating the process of strong gravitational lensing, where the original emitted signal passes close to a lensing object and multiple “copies” of that signal are produced, each with its own path and different magnification. These multiple copies then arrive at the observer on Earth at different times, as distinct signals. The schematic illustrates the effect of strong lensing on a gravitational-wave (GW) source, overlaid on depictions of the effect of strong lensing on light, i.e. an electromagnetic (EM) source: distorted images of the GW source’s host galaxy as they would be observed by telescopes. [Image credit: Laura Uronen, CUHK.]

This means we can search for these multiple lensed signals by looking for gravitational-wave events that seem to display similarities in the parameters we measure for them. For instance, we might observe multiple events that appear to come from binary systems with similar masses, or from a similar direction on the sky, but on first look might appear to be at different distances. Of course there is the possibility that this happens by coincidence, so we must be thorough in our examinations and try to eliminate (or at least reduce) those “false positive” cases. This is done via a multi-stage process.

Firstly, we use rapid algorithms that examine the different gravitational-wave events, looking for these similarities in their inferred parameters and evaluating how compatible different combinations of signals might be under the assumption that they are lensed (referred to as “the lensing hypothesis”). This first step culls the list of lensing candidates that are then passed on to more sophisticated, but more computationally intensive, analyses that seek to determine how significant any potential candidates are.

We must also take into account that, since different signals will have different magnifications, there may be signals detected that are “sub-threshold”: so “quiet” that the LVK’s standard searches for gravitational wave signals would not find them. Nevertheless, they are present within the data we receive and therefore we perform targeted searches for such candidates.

Whilst we most often search for strong lensing on large scales by looking for multiple copies of the same signal, under certain specific conditions it may be that only a single gravitational-wave signal is identifiable. This scenario occurs in what is called the Type II case1, and in these circumstances the lensing results in some small differences in the different frequency modes of the signal which can be detected.

Turning now to smaller, less massive lenses, in this case multiple images are still produced when the signal passes close enough by the object, but because the lens is much smaller so too are the deflections and time delays that the lens produces. This means that instead of multiple separate signals, we observe just one signal that has distinctive so-called beating patterns—where two signals of slightly different frequency interfere with each other. These patterns are theoretically detectable in the LVK data and so we search for them in this study.

What did we find?

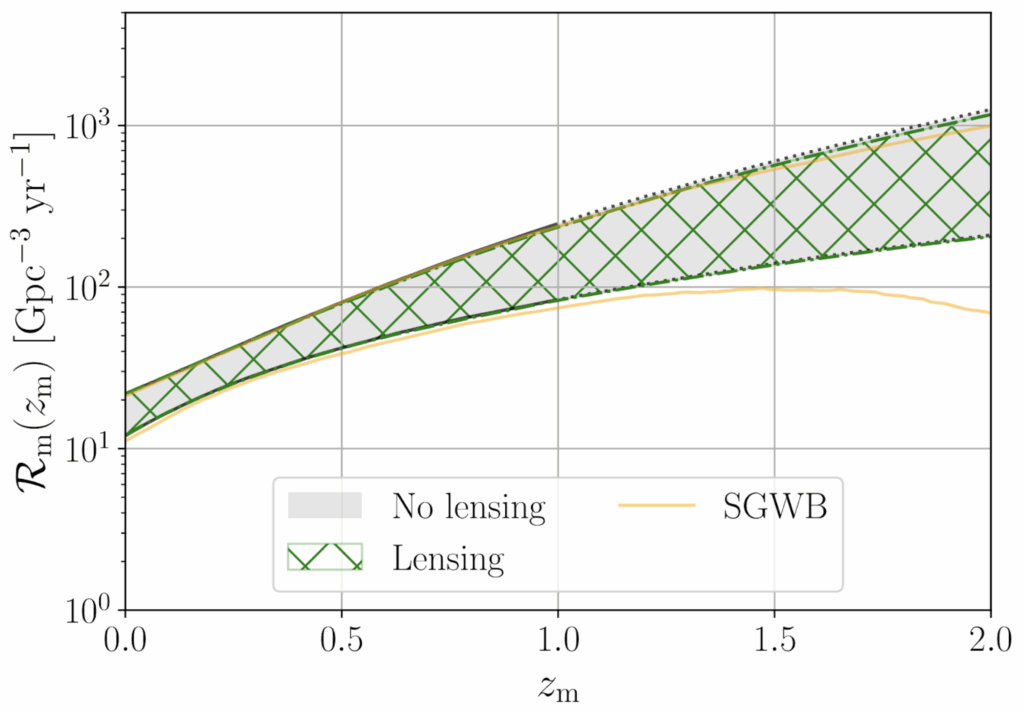

After examination of the almost three and a half thousand pairs of signals that came from combinations of the gravitational-wave sources detected in O4a by our high-speed analyses, only a few tens of these pairs were passed for more intensive study. However, none of these displayed any significant support for lensing and so were discarded. For the subthreshold searches there were also no stand-out candidates. In addition, our Type II strong lensing analysis did not find any significant support for the lensing hypothesis amongst the new events. These results were still useful, however: we used this non-detection of strong lensing to infer constraints on how often binary black holes merge at high redshift, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: (Figure 11 of our paper.) The inferred rate of binary black hole mergers as a function of redshift. Our constraints on the merger rate (shown as the green cross-hatched region) obtained by factoring in the non-detection of strong lensing in this study are comparable with the constraints inferred directly from the properties of black hole binaries that were detected in our new catalog (shown in grey) and with the limits on the merger rate inferred from the non-detection of a stochastic background of gravitational waves (shown by the orange curves).

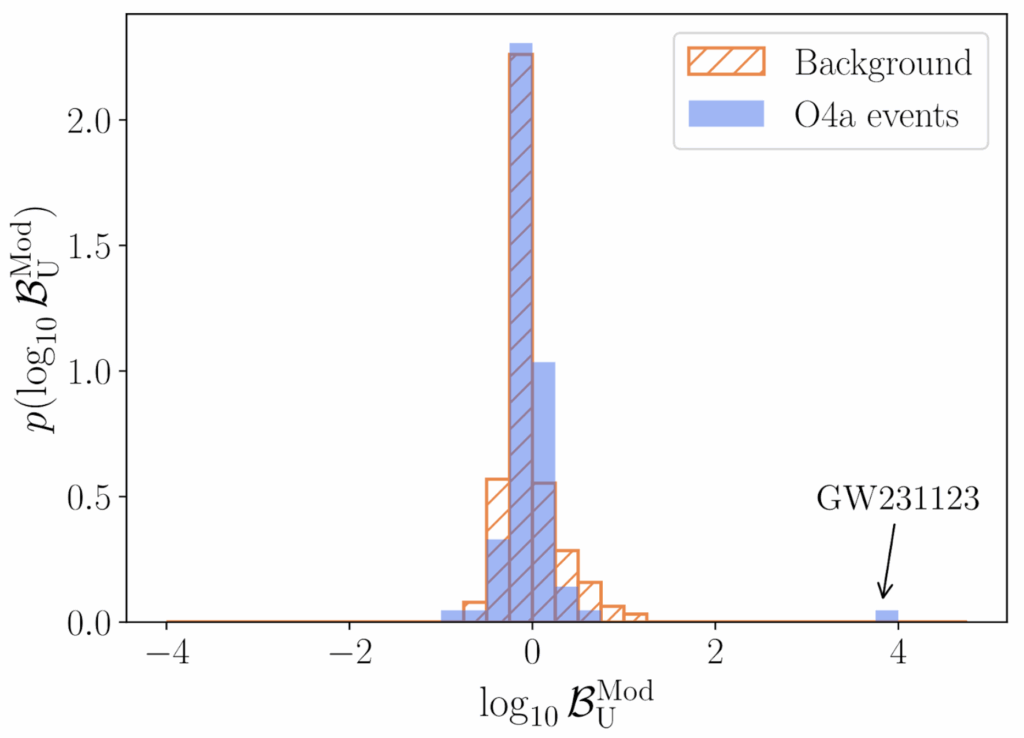

From our search for distortions to individual signals, caused by less massive lenses, the vast majority of signals displayed no support for the lensing hypothesis—showing no distortions beyond the level that could be expected, just by random chance, in a population of unlensed signals. There was a sole exception to this, however: the event GW231123, the detection of which was announced separately as an “exceptional event” ahead of the publication of the full O4a catalog. Our analysis finds that GW231123 seems to display much stronger support for the lensing hypothesis than might typically be expected for an unlensed signal. For example, as shown in Figure 3, after generating a small simulated “background” of just over 250 unlensed gravitational-wave events, we found that none of these simulated events showed the same or greater level of support for the lensing hypothesis as did GW231123.

Figure 3: (Figure 6 of our paper.) The distribution of Bayes factors—which tell us how preferred one model is over another—comparing lensed and unlensed models for the O4a events considered in our study. Shown in blue is a histogram of the (base ten) logarithm of the Bayes factor, comparing a lensed model (where the lens is an isolated point mass) with an unlensed model, for each of our events. Also shown in orange is a histogram of log Bayes factor values for a simulated distribution of just over 250 unlensed events. The majority of the O4a events lie within the simulated distribution. However, GW231123 lies significantly outside of this distribution.

The curious case of GW231123

GW231123 is a very short signal; we observed it for just a few gravitational-wave cycles, over roughly one tenth of a second. From our standard (i.e. assuming no lensing) analyses of this signal, GW231123 appeared to be a heavy, highly spinning black hole binary system (in fact, the most massive such system observed in gravitational waves to date). Puzzlingly, however, the parameters inferred for GW231123 in these non-lensing analyses seemed to vary significantly, depending on the particular model for the gravitational wave emission (referred to as the “waveform”) that was used. On the other hand, when GW231123 was analysed for signatures of lensing these differences between waveform models seemed to be alleviated – and whilst one of the components of the signal was still inferred to be more massive and highly spinning (albeit spinning less than in the unlensed case), the other component appeared to be lighter and spinning more moderately. When analysing a lensed gravitational-wave signal we already know that, if the lensing is not accounted for, this can cause the signal to be inferred as more highly spinning than it actually is. This pattern of behavior would be consistent with what was found for GW231123 if, indeed, this event was gravitationally lensed. However, we must be cautious before jumping to such a conclusion and carefully consider other possible explanations.

One possibility is that, given the shortness of the signal, the quality of the data at some frequencies, associated with particular features in the noise spectrum of our detectors, may be of concern. When we examine the differences between the proposed lensed and unlensed signals for this event, however, this seems to suggest that no single spectral line is responsible for supporting the lensing hypothesis. In a previous case where there was some lensing support in this way, we found that it was driven by the data from just one of our detectors—which suggested that transient noise in that detector, rather than lensing, was the more likely cause. In the case of GW231123, on the other hand, when we examine the data from each of the detectors individually we find that the data still yields support for the lensing hypothesis—meaning that the cause is common to both detectors.

So, if GW231123 is lensed, it’s important to ask “how probable is it that such a lensing system would be observed?” In our study we modelled the object that lensed GW231123 to be an isolated point mass, and there have been recent reports that the Swift satellite may have observed the gravitational lensing of gamma ray bursts by such a point mass lens. While these lensing claims are unconfirmed, if we take them as real they can help us estimate how likely it is that a gravitational-wave lensing event like GW231123 would be observed. In this way (and after factoring in some other possible sources such as Active Galactic Nuclei) we found that we could expect to see a gravitational-wave event lensed by an isolated point mass like that proposed for GW231123 somewhere between one in every hundred and one in every ten thousand gravitational-wave signal detections. In other words, if GW231123 is lensed, then with our current observations it represents quite a lucky find.

On the other hand, we also know that the isolated point mass model used for the searches carried out in our study does not encompass other, perhaps more likely, scenarios for the lens—for example where the lens is embedded within a larger object such as a galaxy. If such a scenario were true, it would change our estimate of how often a GW231123-like lensed event would be observed and more in-depth studies would be required to refine that estimate.

In summary, the results of our analyses when taken together do not allow us to reach a confident conclusion on whether or not GW231123 is genuinely a gravitationally lensed signal. However, in the future, as we observe more and more signals, we may be able to reach that more definitive conclusion, so stay tuned!

Future outlook

The search for gravitational-wave lensing continues! In the latest catalog, we may not yet have found any confidently identified signatures of lensing. However, we have found the most interesting and promising candidate to date in GW231123. In the coming years, as more and more gravitational-wave sources are detected, the prospects look bright for identifying the signatures of gravitational-wave lensing amongst them, and a number of the tests that have been performed in this study will be key to making that identification.

Find out more:

- Visit our websites:

- Read a free preprint of the full scientific article here or on arxiv.

- Gravitational-Wave Open Science Centre data release for GWTC-4.0 available here.

1 In strong lensing there are three classes of “image”. These are called Type I, II, and III. An image is assigned to each of these classes depending on the phase shift it has experienced. This shift may take one of three values: (I) 0, (II) π/2, or (III) π. Which value of phase shift takes place is determined by where in the gravitational field the signal is as it travels along its path towards us.

Back to the overview of science summaries.