Nearly a century ago, Einstein predicted gravitational waves, ripples in space and time that travel at the speed of light, as part of his general theory of relativity. The energy carried by these waves was shown by Hulse and Taylor to be responsible for the inspiral of binary neutron stars, such as PSR B1913+16. Gravitational waves from violent astrophysical systems, such as colliding black holes, can pass by the earth, stretching and squeezing the distances between objects and carrying information about the events that produced the waves, though humans have yet to directly measure the exceedingly tiny effects of these signals.

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) and its international partners Virgo and GEO600 operated as a global network seeking to directly observe gravitational waves from July 2009 until October 2010, after which the construction of major upgrades, Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo, began. This network employed laser interferometers, with extreme isolation from terrestrial sources of noise, to achieve unprecedented sensitivity to gravitational wave signals, allowing scientists to carry out deep searches for astrophysical signals.

Among the sources searched for were compact binaries, systems of black holes and neutron stars that release gravitational waves as they orbit, causing their orbits to shrink and the two stars to eventually collide. Searches for short-lived signals from binaries and from explosive sources such as supernovae require that gravitational-wave signals appear in multiple detectors. The arrival times of the signals must be similar along with their shapes (waveforms). Additionally, LIGO, Virgo and GEO600 data were searched for a continuous release of gravitational waves from isolated spinning neutron stars and from echoes of the very violent universe from times near the Big Bang.

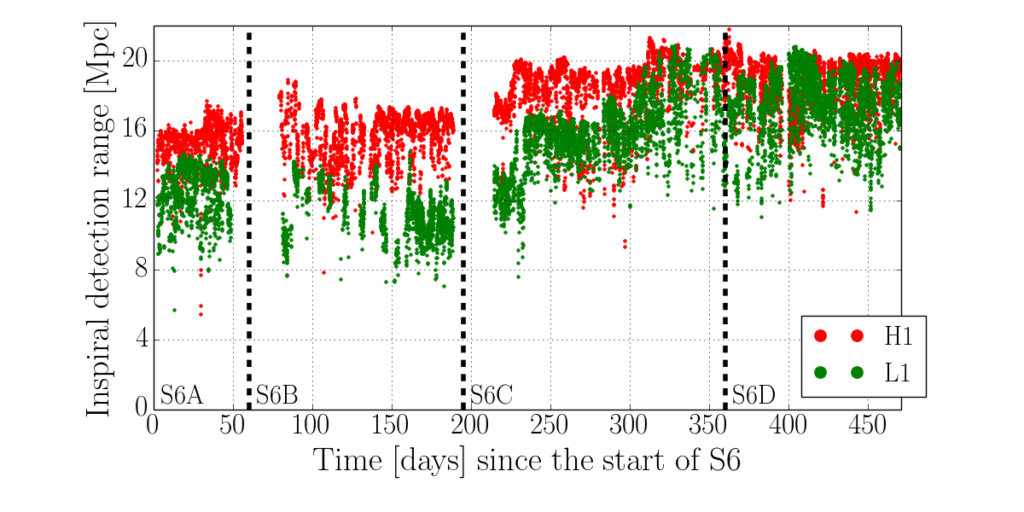

The distance in Mega-parsecs (Mpc, where one Mpc equals 3.26 million light years) to which the LIGO detectors (L1 stands for the Livingston observatory, and H1 for the Hanford observatory) would be capable of detecting a binary neutron star merger, averaged over sky locations and orientation, from July 2009 to October 2010. The distinct improvements between the marked epochs are due to hardware and control changes implemented during commissioning periods.

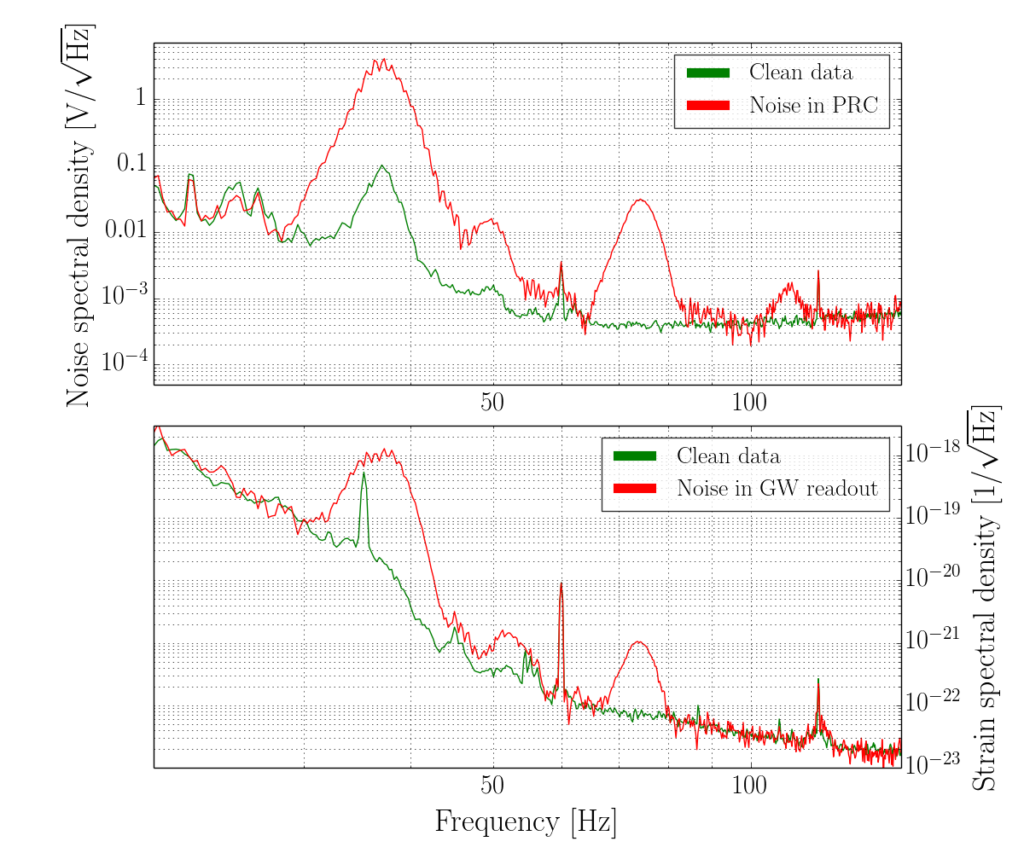

The sensitivity of LIGO’s detectors is determined by their levels of noise. Quieter performance means that the detectors become sensitive to gravitational waves from more distant events. LIGO’s ‘standard’ noise sources in 2009-2010 were seismic vibrations at low frequencies, thermally driven atomic vibrations of atoms in the mirrors at intermediate frequencies, and quantum noise on the laser light at higher frequencies. On top of these ever-present noise sources, additional noise contaminated the data — pops, hums, squeaks and static caused in some cases by the environment and in others by the detector itself. This paper addresses the challenge of identifying and removing these noise events to improve the quality of the detector data.

Example of a data quality issue: LIGO Livingston noise spectrum versus frequency showing (transient) noise peaks centred at 37 Hz and its harmonics in an auxiliary length control signal (top) and in the gravitational-wave output signal (bottom). Each panel shows the spectrum during a noisy period (red) in comparison with a reference taken from clean data (green).

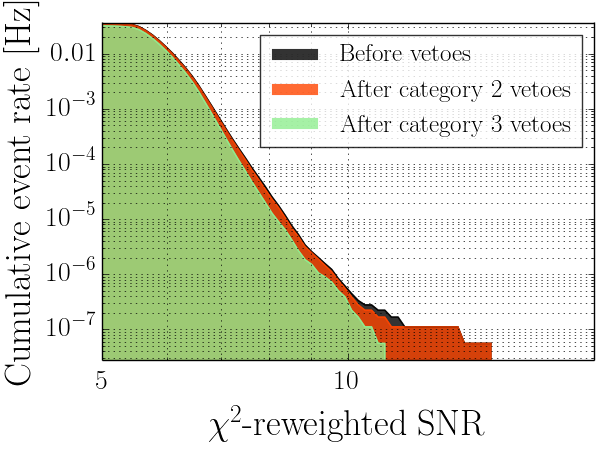

During the gravitational-wave network observing periods, scientists used a combination of statistical techniques and detective work to identify the sources and coupling paths of noise in the instruments and worked with staff at the LIGO sites to ameliorate these as much as possible. A variety of issues were identified as contributing to poor data quality, and many of them were fixed or greatly improved. These included photodiode saturations, seismically-driven non-linear noise, glitching mechanical actuators, poor electrical connections, and electrical pick-up. However, not all of the noise could be removed in this way, and the recorded data still contained noise artifacts that required further (retroactive) cleanup in software. Throughout that process, care was taken to ensure that in reducing noise, potential gravitational-wave signals would not also be selectively thrown away. These combined efforts resulted in a significant cleaning of the LIGO data and thereby an increase in the sensitivity of the searches described above. Although gravitational waves were not directly observed in the 2009-2010 data set, this work improved the astrophysical limits set by searches for compact binary coalescence and gravitational-wave burst sources.

A histogram of candidate binary coalescence events made with time-shifted data to get an accurate estimate of what the detection pipeline would see in realistic data without the possibility of including real gravitational wave events. By vetoing short periods of time with known instrumental noise in the LIGO Livingston detector (defined as categories 2 and 3), many of the loud candidate gravitational wave events (false alarms) are removed.

The Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo detectors are now coming online and will soon have an astrophysical reach that far surpasses what was achieved with the initial detectors. Our best estimates predict that these instruments, when operating at their full performance levels, will together detect roughly 40 compact binary mergers per year. High quality data with minimal noise will be crucial for achieving that performance. The Advanced detectors will also contribute to multi-messenger astronomy that uses gravitational-wave information to direct rapid follow-up by conventional (light-based) telescopes as well as using gravitational-wave data to follow up external triggers. A large effort is underway to improve upon and automate methods to identify and remove poor data quality from the searched data to improve the quality of gravitational-wave alerts published for follow-up.

Read more:

- The publication describing the work

- Similar work that was done focused on the initial Virgo detector